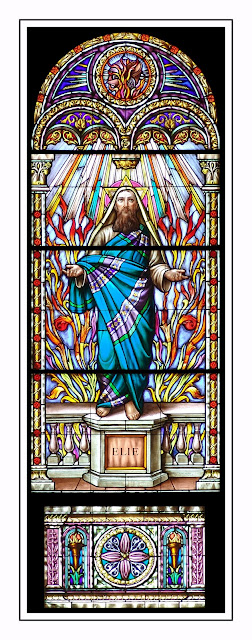

Elijah the Prophet

By http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05381b.htm

“Elias (Hebrew 'Eliahu, "Yahveh is

God"; also called Elijah).

The loftiest and most wonderful prophet of the

Old Testament. What we know of his public life is sketched in a few popular narratives

enshrined, for the most part, in the First (Third) Book of Kings. These

narratives, which bear the stamp of an almost contemporary age, very likely

took shape in Northern Israel, and are full of the most graphic and interesting

details. Every part of the prophet's life therein narrated bears out the

description of the writer of Ecclesiasticus: He was "as a fire, and his

word burnt like a torch" (48:1). The times called for such a prophet.

Under the baneful influence of his Tyrian wife Jezabel, Achab, though perhaps

not intending to forsake altogether Yahveh's worship, had nevertheless erected

in Samaria a temple to the Tyrian Baal (1 Kings 16:32) and introduced a

multitude of foreign priests (xviii 19); doubtless he had occasionally offered

sacrifices to the pagan deity, and, most of all, hallowed a bloody persecution

of the prophets of Yahveh.

Of Elias's origin nothing is known, except that

he was a Thesbite; whether from Thisbe of Nephtali (Tobit 1:2) or from Thesbon

of Galaad, as our texts have it, is not absolutely certain, although most

scholars, on the authority of the Septuagint and of Josephus, prefer the latter

opinion. Some Jewish legends, echoed in a few Christian writings, assert

moreover that Elias was of priestly descent; but there is no other warrant for

the statement than the fact that he offered sacrifices. His whole manner of

life resembles somewhat that of the Nazarites and is a loud protest against his

corrupt age. His skin garment and leather girdle (2 Kings, 1, 8), his swift

foot (1 Kings 18:46), his habit of dwelling in the clefts of the torrents

(xvii,3) or in the caves of the mountains (xix, 9), of sleeping under a scanty

shelter (xix, 5), betray the true son of the desert. He appears abruptly on the

scene of history to announce to Achab that Yahveh had determined to avenge the

apostasy of Israel and her king by bringing a long drought on the land. His

message delivered, the prophet vanished as suddenly as he had appeared, and,

guided by the spirit of Yahveh, betook himself by the brook Carith, to the east

of the Jordan, and the ravens (some critics would translate, however improbable

the rendering, "Arabs" or "merchants") "brought him

bread and flesh in the morning, and bread and flesh in the evening, and he

drank of the torrent" (xvii, 6).

After the brook had dried up, Elias, under Divine

direction, crossed over to Sarepta, within the Tyrian dominion. There he was

hospitably received by a poor widow whom the famine had reduced to her last

meal (12); her charity he rewarded by increasing her store of meal and oil all

the while the drought and famine prevailed, and later on by restoring her child

to life (14-24). For three years there fell no rain or dew in Israel, and the

land was utterly barren. Meanwhile Achab had made fruitless efforts and scoured

the country in search of Elias. At length the latter resolved to confront the

king once more, and, suddenly appearing before Abdias, bade him summon his

master (xviii, 7, sq.). When they met, Achab bitterly upbraided the prophet as

the cause of the misfortune of Israel. But the prophet flung back the charge:

"I have not troubled Israel, but thou and thy father's house, who have

forsaken the commandments of the Lord, and have followed Baalim" (xviii,

18). Taking advantage of the discountenanced spirits of the silenced king,

Elias bids him to summon the prophets of Baal to Mount Carmel, for a decisive

contest between their god and Yahveh. The ordeal took place before a great

concourse of people (see MOUNT CARMEL) whom Elias, in the most forcible terms,

presses to choose: "How long do you halt between two sides? If Yahveh be

God, follow him; but if Baal, then follow him" (xviii, 21). He then

commanded the heathen prophets to invoke their deity; he himself would

"call on the name of his Lord"; and the God who would answer by fire,

"let him be God" (24). An altar had been erected by the

Baal-worshippers and the victim laid upon it; but their cries, their wild

dances and mad self-mutilations all the day long availed nothing: "There

was no voice heard, nor did any one answer, nor regard them as they

prayed" (29). Elias, having repaired the ruined altar of Yahveh which

stood there, prepared thereon his sacrifice; then, when it was time to offer

the evening oblation, as he was praying earnestly, "the fire of the Lord

fell, and consumed the holocaust, and the wood, and the stones, and the dust,

and licked up the water that was in the trench" (38). The issue was fought

and won. The people, maddened by the success, fell at Elias's command on the

pagan prophets and slew them at the brook Cison. That same evening the drought

ceased with a heavy downpour of rain, in the midst of which the strange prophet

ran before Achab to the entrance of Jezrael.

Elias's triumph was short. The anger of Jezabel,

who had sworn to take his life (xix, 2), compelled him to flee without delay,

and take his refuge beyond the desert of Juda, in the sanctuary of Mount Horeb. There, in the wilds of the sacred

mountain, broken spirited, he poured out his complaint before the Lord, who

strengthened him by a revelation and restored his faith. Three commands are

laid upon him: to anoint Hazael to be King of Syria, Jehu to be King of Israel,

and Eliseus to be his own successor. At once Elias sets out to accomplish this

new burden. On his way to Damascus he meets Eliseus at the plough, and throwing

his mantle over him, makes him his faithful disciple and inseparable companion,

to whom the completion of his task will be entrusted. The treacherous murder of

Naboth was the occasion for a new reappearance of Elias at Jezrael, as a

champion of the people's rights and of social order, and to announce to Achab

his impending doom. Achab's house shall fall. In the place where the dogs

licked the blood of Naboth will the dogs lick the king's blood; they shall eat

Jezabel in Jezrael; their whole posterity shall perish and their bodies be

given to the fowls of the air (xxi, 20-26). Conscience-stricken, Achab quailed

before the man of God, and in view of his penance the threatened ruin of his

house was delayed. The next time we hear of Elias, it is in connexion with

Ochozias, Achab's son and successor. Having received severe injuries in a fall,

this prince sent messengers to the shrine of Beelzebub, god of Accaron, to

inquire whether he should recover. They were intercepted by the prophet, who

sent them back to their master with the intimation that his injuries would

prove fatal. Several bands of men sent by the king to capture Elias were

stricken by fire from heaven; finally the man of God appeared in person before

Ochozias to confirm his threatening message. Another episode recorded by the

chronicler (2 Chronicles 21:12) relates how Joram, King of Juda, who had

indulged in Baal-worship, received from Elias a letter warning him that all his

house would be smitten by a plague, and that he himself was doomed to an early

death.

According to 2 Kings 3, Elias's career ended

before the death of Josaphat. This statement is difficult — but not impossible

— to harmonize with the preceeding narrative. However this may be, Elias

vanished still more mysteriously than he had appeared. Like Enoch, he was

"translated", so that he should not taste death. As he was conversing

with his spiritual son Eliseus on the hills of Moab, "a fiery chariot, and

fiery horses parted them both asunder, and Elias went up by a whirlwind into

heaven" (2 Kings 2:11), and all the efforts to find him made by the

sceptic sons of the prophets disbelieving Eliseus's recital, availed nothing. The

memory of Elias has ever remained living in the minds both of Jews and

Christians. According to Malachias, God preserved the prophet alive to entrust

him, at the end of time, with a glorious mission (iv, 5-6): at the New

Testament period, this mission was believed to precede immediately the Messianic

Advent (Matthew 17:10, 12; Mark 9:11); according to some Christian commentators,

it would consist in converting the Jews (St. Jer., in Mal., iv, 5-6); the

rabbis, finally, affirm that its object will be to give the explanations and

answers hitherto kept back by them. I Mach., ii, 58, extols Elias's zeal for

the Law, and Ben Sira entwines in a beautiful page the narration of his actions

and the description of his future mission (Sirach 48:1-12). Elias is still in

the N.T. the personification of the servant of God (Matthew 16:14; Luke 1:17;

9:8; John 1:21). No wonder, therefore, that with Moses he appeared at Jesus'

side on the day of the Transfiguration.

Nor do we find only in the sacred literature and

the commentaries thereof evidences of the conspicuous place Elias won for

himself in the minds of after-ages. To this day the name of Jebel Mar Elyas,

usually given by modern Arabs to Mount Carmel, perpetuates the memory of the

man of God. Various places on the mountain: Elias's grotto; El-Khadr, the supposed

school of the prophets; El-Muhraka, the traditional spot of Elias's sacrifice;

Tell el-Kassis, or Mound of the priests — where he is said to have slain the

priests of Baal — are still in great veneration both among the Christians of

all denominations and among the Moslems. Every year the Druses assemble at

El-Muhraka to hold a festival and offer a sacrifice in honour of Elias. All Moslems

have the prophet in great reverence; no Druse, in particular, would dare break an

oath made in the name of Elias. Not only among them, but to some extent also

among the Jews and Christians, many legendary tales are associated with the

prophet's memory. The Carmelite monks long cherished the belief that their

order could be traced back in unbroken succession to Elias whom they hailed as

their founder. Vigorously opposed by the Bollandists, especially by

Papenbroeck, their claim was no less vigorously upheld by the Carmelites of Flanders,

until Pope Innocent XII, in 1698, deemed it advisable to silence both

contending parties. Elias is honoured by both the Greek

and Latin Churches on 20 July.

The old stichometrical lists and ancient ecclesiastical

writings (Const. Apost., VI, 16; Origen, Comm. in Matthew 27:9; Euthalius;

Epiphan., Haer., 43) mention an apocryphal "Apocalypse of Elias",

citations from which are said to be found in 1 Corinthians 2:9, and Ephesians

5:14. Lost to view since the early Christian centuries, this work was partly

recovered in a Coptic translation found (1893) by Maspéro in a monastery of

Upper Egypt. Other scraps, likewise in Coptic, have since been also discovered.

What we possess now of this Apocalypse — and it seems that we have by far the

greater part of it — was published in 1899 by G. Steindorff; the passages cited

in 1 Corinthians 2:9, and Ephesians 5:14, do not appear there; the Apocalypse

on the other hand, has a striking analogy with the Jewish "Sepher

Elia".”

No comments:

Post a Comment